SOMETHING ABOUT CUBA, ITS HISTORY, ITS CLIMATE, ITS PEOPLE.

By T. B. Thorpe

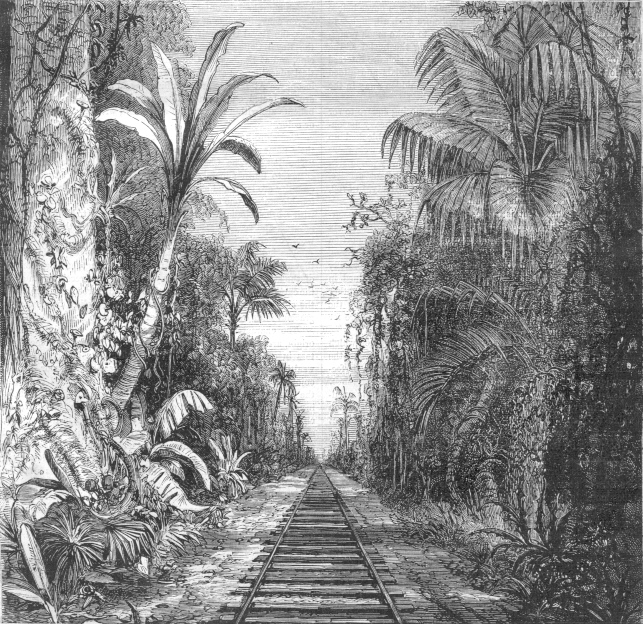

VIEW ON THE ROAD FROM NUEVITAS TO PUERTO DEL PRINCIPE, CUBA.

|

II.

AMONG the principal objects of attraction to a transitory visitor to Havana and vicinity, are the cathedral, the vice-regal palace and gardens, the public square, the opera-house, the Plaza de Toros. The time of the founding of the cathedral seems to be lost to the popular mind, for whether it was built by Velasquez, the first governor of the city, or founded by the Jesuits a century ago, does not seem to be known. It has the impressiveness of size, but it is perfectly free from adornment, the altar and its surroundings being remarkably plain. Its style has been popularly described as being a mixture of the Gothic, Mexican, African, and Moresque, a suggestive description that applies to most of the public and private buildings of Havana. To the American, however, this cathedral possesses an intense interest, for on the left hand side, facing the altar, is a plain tablet, that marks the last and present resting-place of the bones of Christopher Columbus.

The great discoverer died at Valladolid, in old Spain, on the 20th of May, 1566, three centuries ago. His remains, and, by his own request, the chains he was loaded with at Hispaniola, were deposited in a bronze coffin and buried at Seville. From thence, in accordance with his will, they were removed to Hispaniola, at that time the principal city of the New World. In the year 1796, that portion of the Island of Santo Domingo which held his remains was ceded to the French, and the descendants of Columbus caused them to be transferred to Havana, that they might remain under the Spanish flag.

The occasion of our visit to this cathedral was on some memorable church day, the name of which we have forgotten. There might have been three or four hundred of the gentler sex present (not a man of the locality could we see), all kneeling on the variegated marble pavement. The wealthy, including ladies of the highest rank and position, were mingled together promiscuously with the humblest and most poverty-stricken slaves, illustrating, in a manner that was never before so impressively brought to our mind, that, before God, all, high and low, were equal. But this lesson does not seem to make much practical impression on the people in matters regarding the burial of the dead; for we find that in Havana the bodies of the rich are interred within lofty walls, accompanied by pompous ceremonials and gilded inscriptions, while the bodies of the very poor are hidden away in the earth, without ceremony, and without coffins.

There is one fine old church in Havana, the imposing square tower of which is visible from every part of the harbor. The heavy masonry has a dilapidated look. The street in its vicinity is blocked up with old wrecks, and is dusty and deserted. In this church, more than a century ago, while the English were in temporary possession of the city, the Duke of Albemarle used it for Protestant service. After the Spaniards gained possession of the city by treaty, in 1763, the church was shut up, and has remained tabooed ever since.

The history of that event is interesting. The city of Havana surrendered to the British forces after a siege of two months and six days. They occupied Matanzas and Mariel, but a greater portion of the government geographically never recognized the invaders. Cuba was returned to Spain by " the treaty of Paris," and formally given up on the 6th of July, 1763, the English having remained in possession ten months and twenty-four days. Spanish and other writers agree, that this siege and occupation of the island by the British gave new life to the inhabitants, and inaugurated a desire for commercial activity.

One of the most attractive places in Havana is the garden which lies in the centre of the most public square of the city, opposite the Captain-General's palace. Every rare plant here flourishes in perfection, particularly flowers and shrubs of marked beauty and fragrance. This oasis in the midst of the most sultry of cities is entirely unenclosed, the most delicate floral treasures frequently intruding upon the walks trodden every hour by thousands of careless citizens, yet not a tree is barked, nor a plant or shrub is injured—a thing that would be perfectly impossible with any garden thus situated in England or America.

The Plaza de Toros is a circular building, open-roofed, with successive tiers of seats, after the manner of the Colosseum in Rome; it will accommodate fifteen thousand spectators, and is a favorite resort for every class of the Cuban population, to witness their popular amusement of bull-fighting.

The Paseo, situated just outside of the walls of the old city, is a place of popular resort in the evening. It was originally constructed by General Tacon, in the year 1836, but has been adorned and beautified by subsequent governors. It is an oval-shaped, narrow road, of a mile or more in circumference, on both sides of which are raised walks, which serve for a pedestrian promenade. Toward evening the aristocracy here display themselves in their gay volantes; hundreds of these quaint vehicles, each bearing two elegantly-dressed ladies, come out from the city and enter this magic circle, all from the same direction, the procession moving round in a slow and stately manner, while the gentlemen line the raised walks, bow to the ladies, throw bouquets into their laps, exchange friendly' words, or give some important message. All parties seem to enjoy this display. In the mean time, cavalry in white uniforms, indicative of royal troops, are posted along the route to preserve order; but they seem to be equestrian statues, erected for adornment, rather than living men. The idea is a good one, and there might he a Paseo introduced into our Central Park; equipages could thus be displayed to the best advantage, and acquaintances kept up, and, if discipline could be preserved, we have no doubt the fashion would be popular. As an illustration of the social life of Cuba, you will see on the Paseo, once in a while, a gentleman riding with his wife; this open familiarity between the sexes is only laughed at, but creates no scandal; but young ladies and gentlemen thus enjoying themselves would not be tolerated among the native Spanish population of Cuba.

Nearly on the summit of two hills, of gently-sloping declivities, at unequal distances from the town, are two large forts, Cabanas and Principe. In their rear, to the right and left, a landscape studded with neat villas, surrounded by gardens or green spots produced by artificial irrigation, of clumps of orange, cocoanut, palma royal, or other tropical trees. Directly before you is the town—of imposing aspect and extensive dimensions.

The city and suburbs of Havana, a few years ago, contained nine parish churches, six others connected with military orders, five chapels, eleven convents, some of them very large buildings, or groups of buildings, the Royal University, with a rector, and three professors ; also, the Royal College, there being similar establishments at Puerto Principe, and at St. Jago de Cuba, in which several branches of ecclesiastical education are attended to, together with the humanities and philosophy. At Havana are an infirmary and a place for orphans, which are conducted on the most liberal and equitable principles. These benefits are within the reach of all classes, without distinction of caste or color.

The store-keepers in Havana never appear to be anxious to put up their names; the places of business are known as the " Surprise," "The Pet," "The Charm," and by other attractive titles. Linen seems to be in superabundance ; the next thing in importance and quantity are laces and silks. A familiar feature of almost every fashionable store is one or more gigantic white cats, with tails ornamented with a brush similar to a squirrel's. They appear to be quiet and good-natured, and very necessary, it seems, to keep down the vermin, which would otherwise infest the buildings.

The ladies of the higher classes very rarely walk in the streets—they are ever in the volante. If they go shopping, the clerk comes out of the store and inquires what is wanted. Upon receiving an answer, the employe brings the desired article into the street, and displays it on the side-walk ; and, if very desirous of being polite, disposes of it in graceful folds over the dash-board of the volante.

The characteristics of the native population of Cuba, of Spanish origin, are pride and ambition, but differing widely from their ancestors in energy. To northern eyes an effeminate luxury pervades all wealthy classes of Cuba. Symptoms of satiety, languor, and dull enjoyment, are everywhere exhibited—a kind of settled melancholy, the invariable effort of mental and physical inactivity, and an enervating climate. The favorite national amusement of Cuba is dancing. In cities it is conducted in houses, and in public places; in the country, in shady, sequestered thickets, where nature holds the holiday, dancing groups are found. The guitar and tambour on such occasions are seldom silent. Balls are very common, and in rural districts no invitation is needed to attend them—a genteel dress secures a favorable introduction.

Music is also a favorite recreation ; and musical instruments of various kinds, and of extraordinary shapes and tones, are indispensable appurtenances to the boudoir of a Cuban belle. As a rule, guiltless of manual labor, in trifling employments these imprisoned beauties pass their time away.

The more simple of the social amusements of the higher classes are the soft, airy dance of the bayadere to the cheerful sound of the castanets, the fandango, or the more graceful bolero of their father-land The guitar is the favorite instrument of the ladies ; and the pauses and cadences with which the fair Cubanas so feelingly depict, yet so simply mark, the more expressive parts of their plaintive airs, are indescribably soft and soothing, especially when sitting in their verandas in the calm stillness of a moonlight evening.

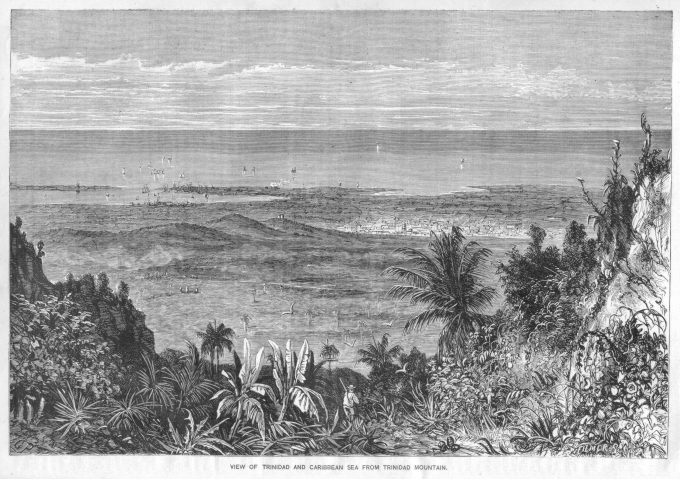

VIEW OF TRINIDAD AND CARIBBEAN SEA FROM TRINIDAD MOUNTAIN.

|

To a Cuban, or even to the European Spaniard, resident of Cuba, it is scarcely necessary to say that smoking is universal—the practice seems to be a requisite of life with all classes, high or low, and is indulged in at all hours, and in every place, at home and abroad. It has been said, with some truthfulness, that the people of Cuba occupy one-third of their time in the preparation of cigars, and the other two-thirds in smoking them. The more respectable classes use cigaritos, inclosed in a neatly-cut piece of the broad leaf of the corn-husk, or of an especially prepared piece of paper. This delicate little cigar is often held by the ladies in a case of gold or silver, which is constantly suspended by a chain or ribbon to the neck. It is absurd to say, whatever we may think of the practice, that the sight of a young girl quietly indulging in the charms of her cigarette, is offensive to look at. There is something very bewitching in the way she holds the object of so much pleasure, and while thus engaged she will, occasionally, so charmingly puff out a delicate whiff of smoke, that it will seem to be a sort of ethereal personification of her wandering pleasant thoughts.

We have seen a stevedore in the harbor of Havana, while engaged in hoisting sugar from a lighter on board of a vessel, suddenly drop out of the crowd at the very moment of their hardest work, and light a cigarette, give it a single puff, and then resume his labor. We have seen a senora in a street car take her seat, light her cigarette, and then attend to the demands of the conductor. We think our druggist, in compounding a prescription for us of three materials, lit his cigarette five times, and gave it the same number of puffs. In passing through the streets, a stranger will be amazed at witnessing the number of persons seen everywhere engaged in rolling up cigaritos, intended for home consumption, or to swell the sum of almost untold millions that find a market in distant lands.

The love for gambling is universal. We do not mean that rude, robber-like display that characterizes the American and English, but a love for games of chance where small sums are won or lost. One meets with some way to risk his silver in all places of public resort and fashionable entertainment. The Havana lottery has a world-wide reputation, and the agents for the sale of its tickets invade every place ; especially are they busy in Havana on Sunday morning, among the crowds who go and come from the cathedrals. Aside from cards, dice, the cockpit, the chances for gaming afforded by the bull-fight are called into requisition.

The Cubans have all the outward regard for the sex that characterizes the Spanish people, and for which their poetry, romance, and history, combine to celebrate. "White hands never offend" is the universal consolation, even where feminine indiscretion becomes ungentle. The Spanish drama is crowded with incidents and beautiful sentiments founded on the extraordinary influence of woman. The power of beauty and the influence of kings are the leading subjects of the Spanish stage.

The large black eye, and raven hair escaping in almost endless tresses ; the dark, expressive glance ; the soft, blood-tinted olive of the glowing complexion, make "the men of the north," in spite of themselves, admit the majesty and beauty of these children of the Spanish race. The Moorish eye is the most characteristic feature; it is full, and reposes on a liquid, somewhat yellow bed, of an almond shape, black and lustrous. In dignity of mien, the Cuban ladies are quite unrivalled. In fact all that is esteemed beautiful in woman in the mother country appears in Cuba softened by the climate and more luxurious social life.

Occasionally, there has appeared, in Havana, a Saxon beauty, blue-eyed, yellow-haired, fair-complexioned—thorough blonde. The effect of such a vision by contrast upon the swarthy, dark, male inhabitants, has been for the time electrical. And, while the gentlemen would wonder at and admire the pearly-hued skin, the light azure eyes, and the streaming golden hair, the haughty brunettes would look on with that disdain that only beauty can affect, and turn away with a majestic step of feminine, yet crushing indifference, that only a lady of Spanish blood can assume.

The full dress of the Cuban ladies seen on the public resorts, is remarkably costly and superb, after the style of old Spain, made up of mantillas and scarfs; and in the hand the never-failing, never-to-be-forgotten, "intelligent, expressive" fan. The colors are sombre, black predominating.

The mantilla, used also as a veil, is usually of black silk or lace,thrown over the head and supported by a high comb, of value and richness, and which always indicates the circumstances or pride of the wearer, leaving the face uncovered, and displaying choice flowers which adorn and contrast with the dark tresses—a style of head-dress which is said to create the graceful and dignified mien and gait for which these descendants of Spain are so celebrated. Hence those who do not wear it, by contrast, appear quite plebeian and commonplace.

Some wear no other head-dress than the hair, variously arranged and ornamented. The most usual way is to plait or roll it in a bandeau round the head, and the crown of which is fastened to a knot, surmounted by a comb, after the manner of the ancient Romans. Some also wear a cap of fine linen, formed like a mitre, over which is thrown the veil, that beautiful emblem of female modesty and elegance. But the most prized and most becoming ornament of Cuban maidens is the trenza, an arrangement of hair in two simple, long, dark, shining braids.

The silk petticoat and the loose white jacket, or short tunic, are worn, when they go abroad. The richness of their dress consists of the finest linen, the most 'delicate laces, and costly jewels, disposed so as to occasion the least inconvenience to the wearer, and producing a perfectly graceful, flowing effect.

But the crowning triumph is the fan ; its size, weight, and splendor, are the pride of the fair possessor. Some are of great value, set with ivory and gold, and ornamented with mirrors. The manśuvring of this fan is a wonder, and comprehends the whole science of the unwritten language of signs, and with it a Cuban lady can carry on an intelligent conversation with the friends of her heart—can express love, disdain, or hate. It flashes a welcome from the quickly-passing volante, a reproof in the ceremony of the Cathedral, an invitation in the blaze of the Opera House.

The men generally may be said to attend to business in the early hours of the morning, their noons being passed in melting lassitude at some Creole coffee-house, the evenings in lounging on the promenade, and at the theatre. Home is only a place of rest, not enjoyment, that can only be had in perfection out of doors.

There are natural causes which produce the peculiarities of Cuban life ; the primal one is the character of the climate, and the consequent necessity of being as much as possible in the open air. The privacy that characterizes the life of more northern latitudes is impossible, and the necessity of calling in menials, to do household duties, with the facilities slavery has afforded to meet the demand, has left the sex in Cuba with but little to do, while the gentlemen, richly rewarded by comparatively little labor, have naturally acquired habits of ease and self-indulgence.

The government of Cuba, though similar to that of the parent state, has always been more oppressive, the Cortes and the Crown having frequently declared that Cuba does not form an integral part of the Spanish monarchy. It has ever been a kind of irresponsible military despotism, or, rather, an oligarchy, in which the love of dominion is carried to a species of fanaticism, and degraded into meanness. The legislative, judicial, and executive power has each been invested in the hands of the governor, and to an extent quite equal to that held by military commanders of a besieged town. Even the higher classes have had no civil rights, such as personal liberty, protection, or right of property, if declared otherwise by the autocrat called the Governor-General.

The Creole population has always been excluded from all influential and lucrative offices. The judges and officials come from Spain, and, being without any stated salaries, they prove so many vultures that prey upon the unprotected within their jurisdiction. There are no means, dishonest, tyrannical, or cruel, that have not been resorted to by the Spanish authorities to fleece the country, and, but for the wonderful productiveness of the island, it would have long since been a desolation.

Notwithstanding the absence of deep rivers, and the unequal fertility of the soil, the island of Cuba, from its undulating character, its ever-springing verdure, and the variety of its vegetable formations, presents on every side a varied and agreeable country. There are five species of palm which make up the body of the forests, and innumerable small bushes, ever laden with flowers, adorn the hills and vales.

Cuba is justly considered even more fertile than any other of the West-India islands. Sugar-cane and tobacco being the staple productions, large establishments for the growth of these articles are scattered over the greater part of the island, forming some of the most beautiful and picturesque features of the landscape.

The cultivated portion of the island is not supposed to exceed one seventeenth of the available land, this latter portion containing large prairies or savannas, in which it is estimated that upward of a million and a half of cattle are reared and pastured. Other parts are occupied by large forest trees, some of which supply the most valuable timber used for practical or ornamental purposes.

To an enterprising, intelligent American, the whole island of Cuba, wherever he goes, constantly suggests facilities for improvement and the accumulation of wealth. As a rule, the island is still almost undeveloped and it is difficult to conceive what it would be, if it were brought under the control of an intelligent and free population.

The space allotted to our imperfect sketch of Cuba, its resources, society, and scenery, is exhausted; no pen can give any perfect idea of this magnificent island, everywhere so attractive and inviting. The magic pencil has been invoked, and, through its charming medium, we have glimpses of those gay, luxuriant views which break upon the traveller as he winds among the hills, more like scenes of fairy enchantment than absolute reality. Everywhere, as we travel in Cuba, new scenes and new views are constantly displaying themselves, yet always presenting, through the receding heights, glimpses of the distant waters of the ocean fading into the blue and cloudless horizon. Once thrown open to the enterprise of the world, Cuba will become in artificial material resources as rich as it has been created by nature, and eventually form a point of the grandest interest in American civilization.

|