Puerto Príncipe – Cuba

By Joseph Alden Springer

U.S. Consular Clerk at

Havana

1875

With Drawings by the Author

Editor’s Note: Puerto Príncipe is now known as Camagüey, the capital of the province of the same name in central Cuba. When this travelogue was written the Ten Years’ War for independence from Spain, which started in and around Puerto Príncipe in 1868, was apparently at a lull. The writer brings an unique American first-hand point of view to an area of the country away from the Capital. The hand-written manuscript was found in the National Archives by Aurelio Giroud. A few changes were made while transcribing the manuscript. They included the addition of footnotes, and many changes to punctuation.

The writer of the following paper had occasion during the past summer to make a

special visit on some private business to Puerto Príncipe, the tierra adentro[1]

of Cuba. As it was a part of the Island that he had never visited, a veritable terra incognita of which he had but

faint ideas—and those not all favorable ones, on account of its being in the

centre of the insurrection—he determined to occupy the spare time that might

otherwise hang heavily on his hands in keeping notes of his trip with the

ultimate idea of printing them; acquiring as much useful and interesting

information as possible concerning a district which was, before the Cuban insurrection,

considered one of the richest on the Island, and which has since done and

sacrificed so much to sustain the struggle of the Cubans for their independence. Considering that this part of the country

has been but little visited by travellers since the outbreak of the

insurrection, and by none has it been fully described, and the subject itself,

from the very interest of it being the base of all Spanish operations in the

Central Department growing on his attention, the writer has devoted

considerable time and taken much pains to have his information correct; and

from various sources of personal observation and other data, has compiled the

following article which he trusts will be perused with interest by the readers

of this magazine.[2]

On a pleasant morning last May, 1874, I took passage at Havana on board

the steamer Cuba, bound to Santiago

de Cuba, but touching at Nuevitas, my point of destination. The steamer was advertised to leave at 12

o’clock and before that hour I was on board and had taken a stateroom which, by

proper “management”—a tip and a wink to the camarero[3]—I

had secured to myself alone, and was then ready for the voyage. But the Government had a large quantity of

stores and provisions to ship by this steamer, intended for the troops at

Santiago de Cuba, and other places on our route, and consequently with

proverbial and provoking disregard for punctuality, the steamer did not get

ready to start until late in the afternoon.

The bell rung, and those who

had come aboard to see their friends off hurried ashore. The steamer backed out

from the wharf, and after a few necessary maneuvers, fairly commenced her

voyage. Directly we had passed out of

the narrow entrance of the harbor and left the Morro Castle to our right behind

us, the table was spread and that agreeable music to a hungry stomach, the

dinner bell, was heard. The table,

extending over the whole length of the skylights on the upper deck, was wide

and well furnished with a profusion of dishes, and although the cooking was

intensely Spanish—oil, olives, and garlic abounding, with decanters of strong,

fiery Catalán wine at every elbow to wash all down with—yet four hours of impatient

waiting to be off, the salt sea air, smooth water, and good appetite compelled

me to do the viands justice. Upon

taking my seat I glanced up and down the table to see who were to be my compañeros de viaje[4],

knowing that dinner was about the only occasion on which all the passengers

would be together at table. A delicate,

sallow-complexioned Cuban lady, who although accompanied by several servant

maids, lugged about a bouncing Negro child of some five years of age whom she

couldn’t have fondled more if it had been her own; a Spanish Colonel with

spectacles on nose and spurs on his heels; a half dozen or so of Spanish

officers, one of whom just from Spain had his wife and little daughter with

him, and all in awe of the Colonel; a priest, who afterwards was dreadfully

seasick and read his breviary all the voyage; several yellow and sea-sickly

individuals; and the writer hereof, made up the complement of passengers.

At no time was the coast

altogether out of our sight, and the weather was delightful, the sea so smooth

and deeply blue, and the breezes so refreshing that the voyage was altogether a

pleasant one. The second night out we

passed the Spanish war steamer Isabel la

Cátolica which had sailed from Havana early in the morning of the same day

we did, bound for Santiago de Cuba, with troops on board, part of whom were to

be landed at Nuevitas.

Early on the third day of

our voyage we passed Martenillos Point, on which there is a lighthouse, and

close to which could be easily discerned the hulk of the Spanish coasting

steamer Triunfo, belonging to Don

Ramón de Herrera—the well known Colonel of the 5th Battalion of

Havana Volunteers—which was lost on the 7th of May last by running

on a reef and while conveying General Cayetano Figueroa, just then appointed to

relieve General Portillo in the Command of the Central Department, and 170 libertos—or Negro troops. As the steamer

but grounded on a reef, and thanks to pleasant weather, no lives were lost.

Rounding this point, in a

short while we arrived at the entrance to the harbor of Nuevitas. On the low sandy beach close to our left,

lay the broken iron frame of the Spanish steamer Cataluña, also belonging to Don Ramón de Herrera, lost a year ago

Christmas.

The entrance to the Bay of

Nuevitas is long and narrow, it being 15 miles from its mouth up to the town.

Vessels drawing 22 feet of water can come into the harbor, but 16 feet is

allowed to be the average depth. About midway off the channel sits San Hilario,

a circular fort of masonry, built in 1831, with several pieces mounted en barbette[5],

and surrounded by a stockade, has been erected as a protection to the

entrance. Several barracks and other

outbuildings are connected with the fort, from the top of which idly fluttered

a ragged Spanish flag. After continuing the devious course of the channel for

about two hours, we finally arrived at our wharf—of which there are four, like

so many long arms stretched from the town—at about 4 o’clock in the afternoon.

But before leaving the

steamer at this point of my narration, I wish to bear witness to the comfort of

traveling in a Cuban coasting steamer, and especially the Cuba.

Although the fare to

Nuevitas may be considered rather high—two doubloons or $34 gold (to Santiago

de Cuba it is three doubloons)—the fare is excellent, and the general welfare

of the passengers is fully looked after, at least judging from my own

experience which was something like the following:

At about 6 o’clock in the morning the camarero, Antonio, would come to my

stateroom, and after a polite “Buenos

Días” hand me a cup of coffee, and a plate of sweet crackers. After discussing this I would be only to

glad to leave my berth—with its hard pillows and cane seat bottom, covered only

by a single sheet in lieu of mattress, which although leaving a beautiful

foetwork on the sleeper’s back and shoulders, would keep him cool during the

night—and go on deck to breathe fresh morning air. On the table on deck would

always be found several suspicious bottles, some long-necked, some

straw-covered, and one a square case bottle of the Bell brand, all open to public inspection. Nevertheless, at 8 o’clock precisely,

Antonio would pass around to the passengers a tray of chin-co-tel or would bring any other kind of an “eye opener” one

would fancy. At 9 o’clock, or a little later, breakfast—the bill of fare

comprising everything. If you disliked the strong Spanish wine, French claret

or ale would be brought instead without extra charge. At midday, the bell would again ring for the passengers to “take

an observation” of the sun’s altitude, which would be done through a cut-glass

tumbler. Dinner at 5, tea at 9 o’clock, and polite and prompt attention to

one’s wishes made those kill-times of a traveler at sea, the pleasures of a

good appetite and strong digestion, passed most agreeably.

But to return from this

digression. Learning that I was too late

to take the daily train to Puerto Príncipe, I inquired my way to the house of

Mr. S., a merchant to whom I had letters, and was just in time to join him at

dinner. After dinner, the Spanish Colonel, who had been my fellow passenger,

made his appearance to call on Mr. S. and shortly afterwards we all sallied out

for a walk around the town.

Nuevitas, or San Fernando de Nuevitas—to give its full name—is a city now of

about 6,000 inhabitants, although in 1868 it counted scarcely 2,500. But this

increase in population is due to numerous families who have been compelled to

come in from the country, where they lived on their cattle farms or subsisted

by selling the produce raised on their small estates or by charcoal burning,[6]

and take refuge in the city from the dangers and privations of the

insurrection. This increase of

population has given no increase in wealth.

On the contrary. I was told that hundreds of families are in the most

abject poverty, only keeping starvation from their doors by occasional labor on

the wharves, the raising of a few vegetables, or the sewing of soldiers’

clothing.

Nuevitas had many

difficulties to contend with in its foundation and settlement, and the present

site is the third within three centuries.

The first was about two miles to the northeast of the city as it now is,

at the place called Pueblo Viejo (Old Town) formerly Puerto del Príncipe, and

was the scene of repeated depredations by the pirates of the Antilles. It is now situated upon several hills and

high ground within the shelter of the bay of some 16 to 20 feet of average

depth. It was the first port on the Island visited by Columbus (on November 18,

1492) during his first voyage of discovery, and called by him Puerto Príncipe.

In November 1511, Diego de

Velazquez was sent by Columbus, son of the great Admiral and Governor at the

time of Santo Domingo,[7]

with an expedition of four ships and 300 men, to conquer and settle the

Island. Here in 1514, in the same port

Columbus had named del Príncipe he

planted a colony and gave to it the name of Santa María. But in the course of time, in consequence of

the plague of insects—the mosquitoes and jejen[8]

(midge) of the period were too much and too many for the sensitive

Spaniards—and the frequent invasions of the pirates—who commenced their

depredations about 1538—the town was transferred to the Indian village of

Caonao. But the inhabitants were not yet secure against the pirates for the

celebrated Morgan afterwards in 1666 sacked the place committing horrible

atrocities.

The frequent invasions of

the pirates—of which Morgan’s attack over a century later was the most

disastrous—had finally induced the colonists to remove still further into the

Island, until in 1516 they reached the Indian town of Camagüey[9],

situated between two small rivers—which to this day retain their Indian names

of Tínima and Hatibonico. And here they rested and built the town for which they

retained the same name: Santa María de Puerto Príncipe, or to give it an

English equivalent, St. Mary’s of Princeport. In the course of time it became

known only by the latter and somewhat anomalous name of Puerto Príncipe. The Indian name of the district is, however,

still retained and it is known to the Cuban insurgents of today as the

Department of Camagüey. For many years Camagüeyano

has been the distinctive term for those born within the district. It is to the Cacique of Camagüey that

Columbus on his first voyage in 1492 sent an embassy, in the belief that he was

the Kublei Khan, or the Emperor of Cathay (China). It is historical that

Columbus died in the belief that he had discovered the Indies and never knew

even that Cuba was an island. In fact this knowledge was not acquired until

1508 when Cuba was circumnavigated by Sebastian de Ocampo.

For nearly a century after

Morgan’s attack, the settlement on the coast gave but little signs of

life. In fact it was almost completely

abandoned or given up to a few fishermen.

The return of a number of families from the interior in 1775 again built

up the town. In the course of time, the migration of the Spaniards from Florida

in 1783, and of the French from Santo Domingo in 1795—to whom are due,

respectively, the introduction of the honey bee and the coffee bean—the natural

increase in population, and the advantages of the port caused the founding of

another settlement on the shores of the same bay.

The construction of a

railroad from Puerto Príncipe to Nuevitas as an outlet for the production of

the district was commenced in 1837, and gave great impulse to the commerce of

both places. This road has the honor of

being the first ever constructed in Spanish dominions, although it was not

finished completely to Nuevitas until 1866.

The port at which formerly the business of the district was done was

Guanaja on the sound or bay of Sabinal some 30 miles to the west of Nuevitas.

The other smaller

settlements dependent upon Nuevitas are Bagá and San Miguel de Nuevitas, both

small towns founded about 1817 by colonists from New Orleans.

It is from Bagá that the

second military Trocha[10]

of the war, to extend across the island, is in process of construction and has

already been completed as far as Gaimaro.

Regarding this Trocha I shall

have something to say further on.

Nuevitas has also received

its share of the suffering caused by the insurrection. Its commerce which in 1868 was 22,000 hhds

of sugar, 15,000 hhds of molasses, a vast number of hides, a great quantity of

wax and honey, and a considerable amount of tobacco—nearly double its exports

of five years previously or in 1863—is now naught. No sugar at all is exported and the small quantity of molasses—an

occasional cargo that is shipped—comes in launches a few hogsheads at a time

from Puerto Padre and other out-ports.

On the 25 of August, 1873,

the insurgents who had for some time previously been in the vicinity, entered

town. The force which the place was

usually garrisoned was 500 men but on this occasion there were not more than

300 counting volunteers. The attack was

made at ten o’clock at night by a strong body of insurgents under the command

of Máximo Gómez, who drove in the sentinels guarding the trenches and stockades

at the outskirts of town near the railroad cutting and swarmed all over the

town. The small force defending the

place together with some marines and volunteers took refuge in the Customs

House, which they defended, and the taking of which the insurgents did not

persist. The patriots kept possession

of the town until six the next morning, in the mean time sacking stores,

setting fire to some of the buildings and having everything their own way.

The Customs House is

situated on the street fronting the bay.

The principal warehouses, stores, British and American Consulates are

also on this street, called Calle de la Marina, and it is clear that the rebels

had possession of the whole town. A

private letter of that date gives an account of the alarm of the inhabitants as

so great that for a number of nights afterwards they abandoned their houses at

nightfall and slept on the wharves, in boats and vessels. But two or three persons lost their lives on

the occasion while the rebels were quite unmolested and their principal object

was plunder, securing quite a booty.

Máximo Gómez, with his staff and the reserve of his force calculated at

600 cavalry, was on a hill near the town and issued his orders with thence.

Ever since the attack, the

inhabitants live in daily fear of a repetition. It is well known that the insurgents are not at any time far

distant and come and go whenever they please, and that their movements are

rapid. A line of forts, connected by a

stockade of light poles for they are nothing else (about 12 feet high and two

or three inches thick) with here and there an occasional redoubt,[11]

has been erected around the city along the upper part of the hills looking

towards the

country as a protection

against future attacks. These forts some eleven or twelve in number are placed

at a distance of half a mile apart. A

number of them are circular in shape built of masonry some thirty feet in

height and twenty in diameter at the base.

A steep ladder leads to the narrow entrance about midway up and the

walls are thickly pierced with loopholes for musketry. On the top a small brass

piece about three feet long and a sentry box are stationed. Sixteen men under a sergeant make up the

garrison of the fort. At night these

men are reinforced by 12 more, generally volunteers. A patrol makes the rounds every two hours. Several detachments of volunteers sleep on

their arms in the Casino and other public buildings. The greatest vigilance is exercised against another attack which

it is supposed may be made any day.

country as a protection

against future attacks. These forts some eleven or twelve in number are placed

at a distance of half a mile apart. A

number of them are circular in shape built of masonry some thirty feet in

height and twenty in diameter at the base.

A steep ladder leads to the narrow entrance about midway up and the

walls are thickly pierced with loopholes for musketry. On the top a small brass

piece about three feet long and a sentry box are stationed. Sixteen men under a sergeant make up the

garrison of the fort. At night these

men are reinforced by 12 more, generally volunteers. A patrol makes the rounds every two hours. Several detachments of volunteers sleep on

their arms in the Casino and other public buildings. The greatest vigilance is exercised against another attack which

it is supposed may be made any day.

But my friend the Colonel,

whom I have lost sight of during this long description, but who gave me much

information—being well informed on all matters pertaining to the history of the

place and of the insurrection—and ourselves, continued our walk chatting on

various subjects until we reached that part of the town near the railroad—where

the insurgents had entered on the occasion previously referred to. Here is built

one of the circular forts in the line of defense around Nuevitas. It is connected with the line built along

the railroad to Puerto Príncipe. Thanks to the three stars on the Colonel’s

cuffs indicating his rank, the sergeant

in command arranged his men in line, saluted, and made a brief report: “No hay novedad, mi Coronel.”[12] The Colonel received it as a matter of

course, made a few enquiries, and then we all mounted the steps into the

interior of the fort. The fort is divided into two stories, the lower being

used for the storeroom, sick bay, and magazine.

The second story is pierced

all around with loopholes, but thirty men in it would make a large crowd. From

this story we ascended a short steep ladder, and through a trap door came out

on the top, from which we obtained a beautiful view of the setting sun and the

scenery so peculiar to Cuba. Along the

railroad track which extended before us, straight as an arrow—it has but one

slight curve in the whole fifty miles—we could see another fort about a mile

off, the second which protects the railroad and the zone of cultivation. To our right was the sheer water of the

Maynabo Sound and the furthest fort of the Nuevitas line of defense, close to

the water’s edge. These forts extending

all around the city—eleven altogether—are all connected by the stockade already

described. They were built by private

subscription among the merchants and others of Nuevitas at a cost of about

$2,000 each, but are manned and armed at the expense of the government.

The next day at noon, while

still occupied jotting down in my notebook the particulars of the various

information I had received from the Colonel, he came for me and advised me to

hurry up, for the explorador would

leave at 12 precisely. Here was a chance for another question while leisurely

putting up my notebook, knowing from experience about Spanish punctuality: It

is aways 12 o’clock until one o’clock strikes, I put it. The explorador is an engine with a fender

attached containing a force of twenty or more soldiers, sent a mile ahead of

the regular train, to clear or “explore” the way. A few minutes walk took us to the station, and after embarking

some two hundred soldiers who had landed during the night from the Isabel la Cátolica which arrived the

same afternoon as ourselves, we entered a car and the train soon started for

Puerto Príncipe. Every car is clad with

a heavy shield of timber three inches thick, bolted on and coming up each side

of the car to nearly the top of the windows, leaving but a small aperture for

either view or ventilation.

Consequently the heat and suffocation are unbearable, and the doors are

allowed to remain open to get a draft through the car, but it affords little

relief.

The train stopped every ten

or twelve miles to take in wood or water, or to leave men or provisions at the

military camps or forts on the way. At Minas, which is situated about half way,

it stopped a full half hour, to leave the soldiers who had been detailed for

the place as laborers on the works of the line. Here an accident happened. The

poor soldiers who had arrived during the previous night had no rations issued

to them nor food of any kind. Some had

managed to get a little wine, which did them more harm than good, making them

noisy and unruly. In stepping from the

car before they came to a stop, one poor fellow fell beneath the wheels and was

fearfully mangled.

The cars were pushed aside

and there he lay, a mass of bruises and broken bones moaning and crying “me muero,” “I die.” An officer brutally

told him to die already and stop making so much noise about it, and then

calling for a litter, had the sufferer picked up and removed. I learned that he did die before he was

carried half a dozen steps, so severe were his injuries.

Minas takes its name from

the proximity of some cooper mines, now unworked It is a place of about 1500

inhabitants, principally country people, who have “presented” themselves to the

Government and to whom it has given lots of land and implements for cultivation

as a means of their support, as to assure their loyalty. But I was informed

that nevertheless small parties are constantly going back into the

insurrection. The place is built up

altogether of thatched houses, and the only business done is that naturally

arising at a military depot and camp.

The mines, which were said

to have been rich in the yield of copper, and the exploitation of which was due

to enterprising Americans, are now now longer worked. It is believed that if the facilities for transportation were

easier and cheaper, copper could again be produced at a profit “when this cruel

war is over.”

Some 1500 soldiers are

stationed here, engaged in the labor of building forts and fortifying the line.

This number added to the 1500 required to garrison all the forts, makes a force

of 3,000 men constantly engaged to hold the line of railroad between Puerto

Príncipe and Nuevitas and keep the insurgents in check. Nevertheless I am told they pass it in small

parties almost daily, but do not hazard useless attacks upon the forts.

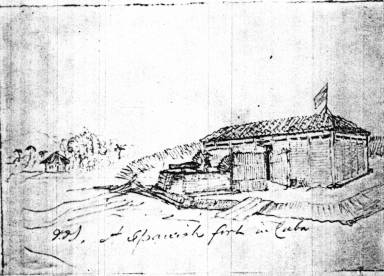

These forts, nearly fifty in

all, are stationed a mile apart. Some

are stockaded and others have the addition of a ditch. Some are built of palm tree logs or slabs

and others again of brick, but almost all present the peculiarities of the one

shown in the accompanying sketch.

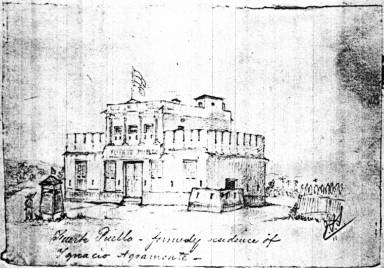

Just before reaching Puerto

Príncipe, the Colonel, who throughout the trip had been talking away to my

great interest—abusing the insurgents, their plans and operations, but giving

me considerable information regarding affairs—called my attention to a fort,

the last before arriving the city, as having been formerly the residence of

Ignacio Agramonte, the insurgent chieftain who was killed at the head of a

charge of cavalry at Jimaguayú on the 11th of May, 1873.

This fort, converted into

such from a plain country residence—its upper walls built up and loopholes

pierced through the masonry. I determined to make a sketch of it and did so on

a later occasion at the cost of a little adventure which I will here relate:

I walked along the railroad track

to within a short distance of the safe side, took up a favorable position and

began my sketch. After a while my

movements seemed to have attracted attention and two civiles sauntered out and looked over my shoulder making polite but

critical observations as I progressed.

Their presence made me nervous and I hurried to finish my sketch. Then putting up my book, I begged them “to

remain with God,” and started back to the city. A backward glance revealed the two worthies with heads together

and a minute later I was called upon to come back. Very politely they regretted

to have to deliver up my “picture” for the inspection of the Primero or Sergeant in Charge.

“Certainly, but bring it back quick and meantime I’ll make a sketch of this

country tienda.” After a few minutes

delay, the

I walked along the railroad track

to within a short distance of the safe side, took up a favorable position and

began my sketch. After a while my

movements seemed to have attracted attention and two civiles sauntered out and looked over my shoulder making polite but

critical observations as I progressed.

Their presence made me nervous and I hurried to finish my sketch. Then putting up my book, I begged them “to

remain with God,” and started back to the city. A backward glance revealed the two worthies with heads together

and a minute later I was called upon to come back. Very politely they regretted

to have to deliver up my “picture” for the inspection of the Primero or Sergeant in Charge.

“Certainly, but bring it back quick and meantime I’ll make a sketch of this

country tienda.” After a few minutes

delay, the  Sergeant came out with the

sketch in hand, took a good scrutiny of me. Then to my rather impatient inquiry

if there could be any objection to my keeping the rude design I had made gave

it a critical examination, and seeing nothing about it to resemble a plan of

military fortification gave it up, begging pardon for the trouble I had been

caused, which was due to the exceptional times. I again availed myself of a

Spanish figure of speech and consigned the whole party “to the care of

God.” They returned my politeness by

wishing me “God be with ye” or goodbye.

I started back on the track fully expecting another hail, but determined

on this occasion to be deaf.

Sergeant came out with the

sketch in hand, took a good scrutiny of me. Then to my rather impatient inquiry

if there could be any objection to my keeping the rude design I had made gave

it a critical examination, and seeing nothing about it to resemble a plan of

military fortification gave it up, begging pardon for the trouble I had been

caused, which was due to the exceptional times. I again availed myself of a

Spanish figure of speech and consigned the whole party “to the care of

God.” They returned my politeness by

wishing me “God be with ye” or goodbye.

I started back on the track fully expecting another hail, but determined

on this occasion to be deaf.

After four hours of the

uncomfortable traveling in the cars which I have described, we arrived at

Puerto Príncipe. Just before reaching the station the engine gave four

prolonged shrieks as a signal to the city that the steamer from Havana had

arrived at Nuevitas and mail might be expected. This I learned was the custom,

three shistles announcing the arrival of a steamer from Santiago de Cuba, four

from Havana and seven for two steamers arriving, one from each place.

A number of the Colonel’s

friends were on the platform to welcome him, and while they were throwing their

arms around him and patting him on the small of the back, an orthodox Spanish

embrace, I took my leave, got a volanta,

and drove to a Hotel.

Puerto Príncipe, or to quote again its full name:

Santa María del Puerto del Príncipe, is a city situated in one of the

widest parts of the Island of Cuba, a distance of 325 miles in a southeast by

east direction from Havana. Thirty miles from its old port of Guanaja on the

north coast, 60 miles from Santa Cruz on the south coast, and 45 miles from

Nuevitas with which it is connected by a railway. Its population in 1868 was estimated to be about 35,000 souls and

the present population cannot be much less, for unless there has been a great

exodus of its inhabitants into the insurrection, yet many of those who had

fixed residences in the country have been compelled to come into the city to

live.

The district was

preeminently the cattle and breeding farm of the Island, which constituted its

principal wealth. Before the war nearly two million head of cattle roamed over

its rich pastures and its mules and horses were preferred to any others. The district never was remarkable for

production, either of a textile or fabrile nature, on account of want of water

carriage. It was only comparatively

late that attention was paid to cultivation of sugar molasses. The figures

given on previous pages as from Nuevitas is understood to be the production of

the entire district. In 1868 there was

calculated to be about 150 sugar plantations of more or less extend, and nearly

as many tobacco vegas within the

jurisdiction. Now the blight of war rests upon everything: of the sugar

plantations, all have been abandoned save one close to the city called Canet. Formerly it made 1000 hhds. for a

crop, but now it can barely make 300, not enough to supply the district. The

tobacco fields are destroyed, not a pound of honey or wax is gathered, and

general ruin has settled over this department.

The inhabitants formerly were noted for their gay and lively dispositions,

and if not immensely rich, were all well off.

Now what few that have not gone into the insurrection have a listless,

apathetic and poverty-stricken look.

The city was formerly a basin of supplies for the plantations and cattle

ranchers, and the principal inhabitants passed their time between their country

and town houses, riding fine and blooded horses. Now no business or any account is done, and the houses one sees

are the sorriest of nags.

The area of the city

comprises of some hundred or more acres and its streets, narrow and crooked,

are laid out in a bewildering maze forcing one to believe that, like those of

Boston tradition, they have been determined by the cow-paths. The houses are low, with the Cuban

peculiarities of tiled roofs, heavy doors and gated windows—although the same remark

may apply to all houses of Spanish architecture—and are almost without

exception built of brick—which is in fact the only building material used—there

being no quarries but numbers of tejares

or brickyards in the vicinity. The

bricks are long, wide, thickly covered between as is to save material, and then

plastered over. The walls are painted,

blue and buff being the prevailing colors. There are but few houses of two

stories in height. The sidewalks, or

what passes under that name—for they are exceedingly narrow and of uneven

height—are also of brick, set on end, and often through use half worn

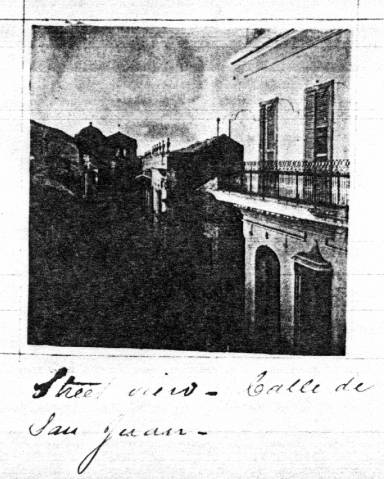

through. I obtained a photograph of one

of the streets—Calle de San Juan—which

will show some of their peculiatiries and which in fact was the  only photographic view I

could find on any part of the city. No interest has been taken in views of that

nature, and despairing of obtaining any at all, I had recourse to my own pencil

to depict some of the public buildings. But few streets are paved or

macadamized, but all are generally clean and seldom muddy on account of the

porous sandy nature of the soil which eagerly drinks up the heavy rains of this

period of the year. There are no wells.

The greater part of potable water is caught and preserved in cisterns or tinajones, large earthen jars kept on

the roofs or in couryards of the houses.

The streets are not lighted at night at the public expense, but it is

the general custom for everyone to hang before his door a glass lantern with a

petroleum lamp. The principal streets are consequently well lighted, while

others remain in total darkness.

only photographic view I

could find on any part of the city. No interest has been taken in views of that

nature, and despairing of obtaining any at all, I had recourse to my own pencil

to depict some of the public buildings. But few streets are paved or

macadamized, but all are generally clean and seldom muddy on account of the

porous sandy nature of the soil which eagerly drinks up the heavy rains of this

period of the year. There are no wells.

The greater part of potable water is caught and preserved in cisterns or tinajones, large earthen jars kept on

the roofs or in couryards of the houses.

The streets are not lighted at night at the public expense, but it is

the general custom for everyone to hang before his door a glass lantern with a

petroleum lamp. The principal streets are consequently well lighted, while

others remain in total darkness.

The sidewalks are uneven in

height and the streets so narrow that most of the walking is done in the street

itself. The houses are, Cuba fashion,

closed during the day. But as evening comes on doors and windows are opened,

and the ladies freshly and simply dressed and generally wearing flowers in

their hair sit at them to enjoy the cool of the evening and receive their

visitors. On many of the grated windows

I noticed the dried up remains of the elaborate palm branches used on the

festival of Palm Sunday, which must hve made that holiday most attractive. I witnessed the processions of Corpus

Christi and some other religious holidays during my stay. After leaving the Church, at every block or

two en route, there would be erected rich and glittering altars in front of

private houses before which the procession would generally stop and perform a

short ceremony. Little children gaily dressed, scattered flowers along the

way. The Host was carried by richly

robed priests, who walked under a cloth of silver baldachin. The Governor and City Council, a number of

officers in uniform, the school children and the members of one or two regional

societies took part in the procession, followed by a detachment of cavalry and

infantry volunteers.

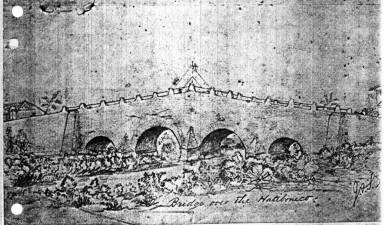

The rivers Tínima and

Hatibonico, between which the City is situated, would not in the United States reach the  dignity of creeks. But after a heavy rainfall swell so rapidly

as to completely overflow even their arches, as shown in the accompanying

sketches. Their beds may be estimated

from the span of the bridges. During my

stay in the city it rained often and heavily.

The Hatibonico on one occasion not only rose above the arches of the

bridge, but overflowed its banks into the streets adjoining. Both bridges are solidly built and entirely

of brick. Near that over the Tínima

river the country is flat and plain. Close by is situated the casa quinta, or country house and

tannery of the Simoni family, now used as a fort and guarded by a detachment of

volunteers. It is showing the

dignity of creeks. But after a heavy rainfall swell so rapidly

as to completely overflow even their arches, as shown in the accompanying

sketches. Their beds may be estimated

from the span of the bridges. During my

stay in the city it rained often and heavily.

The Hatibonico on one occasion not only rose above the arches of the

bridge, but overflowed its banks into the streets adjoining. Both bridges are solidly built and entirely

of brick. Near that over the Tínima

river the country is flat and plain. Close by is situated the casa quinta, or country house and

tannery of the Simoni family, now used as a fort and guarded by a detachment of

volunteers. It is showing the  usual neglect and vandalism;

the fences torn down, horses feeding in the garden, loop holes pierced through

the walls, and the house gradually gone to ruin.

usual neglect and vandalism;

the fences torn down, horses feeding in the garden, loop holes pierced through

the walls, and the house gradually gone to ruin.

Many of the rich inhabitants

who had not joined the insurrection have yet been ruined by its consequences. Along with the poorer class the suffering is

from poverty is great. During the long walks I made around the city and

especially the suburbs where the houses are of poorer and meaner character, it

was sad to see through the half-open door of many: lying upon the floor a bunch

of plantains, half a squash, a few fruits, and perhaps half a dozen eggs;

waiting for a purchaser. The number of

ragged and naked children of all shades of color I saw during my rambles was

something to wonder. Many of the women

support themselves by sewing on soldiers’ clothing. The pricing for making shirts in April was $1 in Spanish currency,

per dozen; and half of that to be taken in trade. But General Figueroa, who had recently taken command of the district,

insisted that the different establishments should pay $1.50 per dozen in

cash. With gold at 260 as it is now,

the misery of such wages is apparent, and when it is considered that eggs cost

12 cents, a roll of bread 10 cents, a sweet 20 or 30 cents, sugar 25 cents per

pound, and beef $3 to $4 , and

everything else in the same proportion; it is a wonder that the poorer class

can live at all.

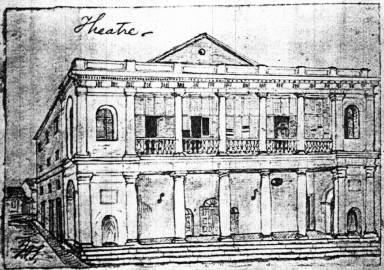

During my stay, for

amusements, I attended a performance at the Teatro Principál and several Balls

at the Casino Español. The performance

at the theatre was given by a number of clever amateurs in aid for the fund for

wounded soldiers. The house was very well filled, principally by Spanish officers

in the parquette, a few ladies in the boxes, and the “military” in the upper

circles. To judge from the sound made

by their feet over the uncarpeted wood floors like a squadron of Calvary, the

acoustic qualities of the building are excellent. The theatre outside has an imposing exterior, but the entrance

doors are disproportionately small.

Inside it will seat nearly 1000 people, has four tiers, and is lit by

coal oil lamp sconces hung in front of the boxes. The play, which was something

about “Love and Interest,” went off acceptably but the performance did not

commence until nearly nine o’clock.

The Theatre was built in

1849, entirely of brick and plastered over, and opened its first season with an

Italian Opera Company. Parodi, Corbesi,

Alamo, Lorini, Patti when a child; the tenors Tiburini, McCaferri, Musiani and

others in opera; and the Spanish drama interpreted by Matilde Diez, Ossorio,

Valero, etc. have in former times delighted the pleasure-loving Camagüeyanos.

But with the war came a change. The

Theatre was deserted for a while, then utilized for a short time as barracks

for Volunteers, and now the building now shows signs of neglect in its broken

blinds, plaster dropping from walls and ceilings, and the empty niches formerly

adorned by statues of the Spanish Drama Lope

de Vega, Moratín, and others.

The Theatre was built in

1849, entirely of brick and plastered over, and opened its first season with an

Italian Opera Company. Parodi, Corbesi,

Alamo, Lorini, Patti when a child; the tenors Tiburini, McCaferri, Musiani and

others in opera; and the Spanish drama interpreted by Matilde Diez, Ossorio,

Valero, etc. have in former times delighted the pleasure-loving Camagüeyanos.

But with the war came a change. The

Theatre was deserted for a while, then utilized for a short time as barracks

for Volunteers, and now the building now shows signs of neglect in its broken

blinds, plaster dropping from walls and ceilings, and the empty niches formerly

adorned by statues of the Spanish Drama Lope

de Vega, Moratín, and others.

The first Ball at the Casino

had been postponed several times on account of rain and finally given the

evening previous to St. John’s day.

This day and in fact the whole month has in former years—and especially

before the insurrection—been celebrated with one long round of pleasure. The

custom seems to have been peculiar to Puerto Príncipe alone of all the Island.

It has been described as the Carnivals of Rome, Venice, and Paris rolled into

one and lasting a month. The description

given to me of former glorious San Juans

made even the pageants of Mardi Gras in New Orleans pale before it.

Balls and parties lasting

for days altogether, cavalcades, masks, processions in costumes of mythologic

or historic tunes, reunions on every side, good cheer, good humor and good

temper abounding, and a profuse and lavish display and expenditure, made this

month the gayest of the year and Puerto Príncipe the jolliest place in the

Island. But now, how changed! The custom has probably died out forever – I saw

nothing to resemble the former festivity of this period. They now have the

regimental bands, dressed up outré

costumes of cheap colored calico and high comical paper hats, which went about

playing and collecting funds for wounded companions; and a few dancing parties

in private houses. The Balls given at the Casino were very well attended,

Spanish uniforms abounding. The simple dresses of the ladies gave them fresh

charm and I noticed many beautiful faces.

The Colonel said, however, after a critical stare around the room

through his spectacles, that the pretties ones had all gone away since the

insurrection or else would not attend the Spanish

Casino, having lost relatives and friends on the war; and that, in short, like

everything else since that event, San

Juan was played out.

The Casino Español—Spanish Club—of Puerto Príncipe is, like the

remainder of the Casinos in the Island—some thrity five in all—in certain

measure dependent upon the Casino Español

at Havana. Like them, it is considered the centre and representative of the

Spanish element. It is used as a place of social meeting, amusement, and other

purposes of a club, and—when occasion offers—for the expression of political

opinion. It has refreshment and billiard rooms on the ground floor. On that above, a reading room, a small

stage, and quite spacious saloons are handsomely provided with elegant furniture

including two grand pianos. The walls

are profusely decorated with mirrors eight and ten feet square in heavy gilt

frames. The tawdry red and yellow of the Spanish colors form curtains and valances

for the doors and windows, and the Spanish coat of arms is conspicuously

displayed. The main saloon is further

adorned with an allegorical painting representing the city with the portrait of

a particularly fierce-looking bestarred and laboned individual, which the Colonel said was that of Don Pedro Caso, a

former General Commander of the Department.

The Casino Español—Spanish Club—of Puerto Príncipe is, like the

remainder of the Casinos in the Island—some thrity five in all—in certain

measure dependent upon the Casino Español

at Havana. Like them, it is considered the centre and representative of the

Spanish element. It is used as a place of social meeting, amusement, and other

purposes of a club, and—when occasion offers—for the expression of political

opinion. It has refreshment and billiard rooms on the ground floor. On that above, a reading room, a small

stage, and quite spacious saloons are handsomely provided with elegant furniture

including two grand pianos. The walls

are profusely decorated with mirrors eight and ten feet square in heavy gilt

frames. The tawdry red and yellow of the Spanish colors form curtains and valances

for the doors and windows, and the Spanish coat of arms is conspicuously

displayed. The main saloon is further

adorned with an allegorical painting representing the city with the portrait of

a particularly fierce-looking bestarred and laboned individual, which the Colonel said was that of Don Pedro Caso, a

former General Commander of the Department.

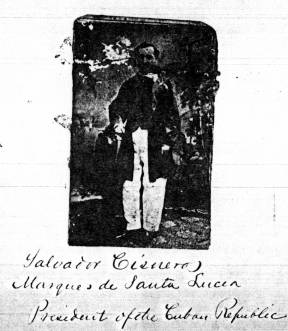

The Casino occupies a

building which was once the property and residence of Salvador Cisneros, Marqués de Santa Lucía, now known as the

President of the Cuban Republic.[13]

Afterwards this building was the location of the Sociedad Filarmónica which before the insurrection was distinguished

for the high position of its members—principally the Cuban families—and the

artistic merit of its musical and dramatic entertainments. Many of its members

joined the insurrection and the society was repressed. The building was unsed

in 1869 as a hospital for the wounded soldiers of Col. Lesca’s column, and the Guias de Rodas, a body of volunteers

acting as a bodyguard for Captain General Rodas was also billeted in it. The

Casino was established in 1870.

The Casino occupies a

building which was once the property and residence of Salvador Cisneros, Marqués de Santa Lucía, now known as the

President of the Cuban Republic.[13]

Afterwards this building was the location of the Sociedad Filarmónica which before the insurrection was distinguished

for the high position of its members—principally the Cuban families—and the

artistic merit of its musical and dramatic entertainments. Many of its members

joined the insurrection and the society was repressed. The building was unsed

in 1869 as a hospital for the wounded soldiers of Col. Lesca’s column, and the Guias de Rodas, a body of volunteers

acting as a bodyguard for Captain General Rodas was also billeted in it. The

Casino was established in 1870.

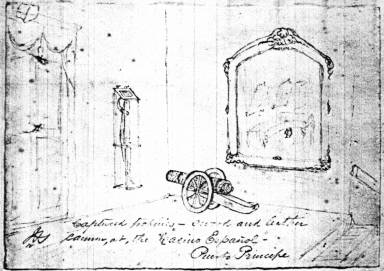

Upon ascending the staircase the first objects to attract one’s

attention, standing in a corner of the saloon at the head of the steps, are a

sword in a glass case and a small cannon, which on examination proves to be

made of leather. I thought them of

sufficient interest to merit a sketch.

The sword is a plain but heavy Toledo Cavalry Sabre, without a scabbard

The glass case in which it is contained bears a card with the following

inscription:

Espada cojida al enemigo por el Batallón Peninsular Cazadores de Pizarro al mando del Primer Gefe, Teniente Coronel

Don Juan Francisco Moya, en el potrero San Antonio de Consuegra, el dia 11 de

Mayo de 1872, que el Excmo. Señor Capitán General Don Pedro de Lea y

satisfaciendo los deseos del Sr. T. Col. Moya, regala al Casino Español de

Puerto Príncipe — Junio 13, 1872.

Espada cojida al enemigo por el Batallón Peninsular Cazadores de Pizarro al mando del Primer Gefe, Teniente Coronel

Don Juan Francisco Moya, en el potrero San Antonio de Consuegra, el dia 11 de

Mayo de 1872, que el Excmo. Señor Capitán General Don Pedro de Lea y

satisfaciendo los deseos del Sr. T. Col. Moya, regala al Casino Español de

Puerto Príncipe — Junio 13, 1872.

Which may be thus translated:

Sword captured from the enemy by the Peninsular

Battalion Chasseurs de Pizarro, under

the command of its first officer Lt. Col. Juan Francisco Moya on 11 May 1872 at

the pasture San Antonio de Consuegra,

an which the Commander General Don Pedro de Lea, counting upon the consent of

His Excellency the Captain General and the wishes of Lt. Col. Moya, presents to

the Casino Español of Puerto Príncipe

— Jule 13, 1972.

The cannon is about three feet

long, three inches in diameter, at the mouth an inch thick, and is made

throughout of leather; truly, there’s

nothing like leather. It appears to

have been made by binding and twisting bands of raw leather hide around the

center piece—which is entire and smooth throughout its bore—into a sort of

basket twist until the piece was bout an inch thick and a few bands of plain

hoop iron added to fix it to its wooden carriage. Not a very formidable piece

on appearance, but capable with a small charge of throwing a shell or grenade

some distance. I was informed by the Colonel that the insurgents made a number

of such pieces, but that they soon became worthless on account of the

deterioration and rotting of the leather. The piece in question, as is stated

on a card attached in the same high-sounding phraseology, was captured from the

enamy at the Najasa Ridge on the 31st of December 1871 by the

Batallion of San Quintin commanded by Col. Luis de Cubas and presented to the

Casino “in proof of the union which exists among Spaniards whenever the defense

of their flag is at stake.”

The Casino has about 300

paying members and is much frequented in the billiard and coffee rooms by

Spanish officers, whilst the library and reading room bears evidence of

shameful neglect.

I had invited the Colonel to take a

drive with me for the purpose of getting him to point out the different public

buildings. So one pleasant afternoon we

engaged an immense wheeled volanta

with a ridiculously small animal of the mule species for motive power and a

ragged negro boy as engineer, and off we started.

I had expressed a desire to

see the various churches so we commenced with them, first going to the Plaza de Armas near which is situated

the Casino Español, and passing the Post Office and Government House on our

way, looked at the Iglesia Mayor, or

First Church. This was the site of the first church built in the city, which

was destroyed by fire in 1616 and rebuilt in 1617, although not receiving its

present and completed form until 1794. It is now used as a military hospital

and contained about 200 sick and wounded soldiers.

I had expressed a desire to

see the various churches so we commenced with them, first going to the Plaza de Armas near which is situated

the Casino Español, and passing the Post Office and Government House on our

way, looked at the Iglesia Mayor, or

First Church. This was the site of the first church built in the city, which

was destroyed by fire in 1616 and rebuilt in 1617, although not receiving its

present and completed form until 1794. It is now used as a military hospital

and contained about 200 sick and wounded soldiers.

Next we went to the Convent

and church of Nuestra Señora de la Merced[14]

on Market Square. This convent was founded in 1601, but it is now used as

barracks for Spanish soldiers. The church is one of the finest on the Island

but was not finally completed until 1759. It boasts one of the highest towers

of any church in Cuba and the only wood in its construction is in the doors and

windows. It was remodeled and repainted in 1844 and is the custodian of

valuable silver altar pieces, a silver throne for Our Lady, and a silver Holy

Sepulchre said to be made of much artistic merit and value.

The church of La Soledad[15]—built

in 1776—being close to our hotel we could see daily, so we drove to the church

of Santo Cristo del Buen Viaje—built

in 1774—to which in 1812 the public Cemetery was attached. Here we left the carriage

for a while to look on with amusement at efforts of a drill sergeant to teach

the mystery of the goose step to a very awkward squad of liberto troops, all of whom were armed with the heavy machete[16].

We also strolled into the Cemetery and I was agreeably surprised to see the

elegant and tasteful resting places of the dead so different from the repulsive

tiers of ovens—or niches, as they are called—of the Havana cemetery and

generally others in the Island. Monuments, marble figures, carved gravestones,

tombs in shape of domed mosques, stone slabs over graves surrounded by iron

railings, memorial tablets let into the church walls in the cemetery, and other

mementos of the dead, all in good taste; and the melancholy sound of the wind

through the tall pines made a pleasant impression in one who expected to meet

again the formal and stereotypical form of ovens, one above the other, of the

receptacles for the dead prevailing in other Cuban cemeteries. I walked about

and noticed such names as Agramonte, Aguero, Betancourt, Varona, Mola and other

familiar enough in the annals of the Cuban Insurrection.

The church of La Soledad[15]—built

in 1776—being close to our hotel we could see daily, so we drove to the church

of Santo Cristo del Buen Viaje—built

in 1774—to which in 1812 the public Cemetery was attached. Here we left the carriage

for a while to look on with amusement at efforts of a drill sergeant to teach

the mystery of the goose step to a very awkward squad of liberto troops, all of whom were armed with the heavy machete[16].

We also strolled into the Cemetery and I was agreeably surprised to see the

elegant and tasteful resting places of the dead so different from the repulsive

tiers of ovens—or niches, as they are called—of the Havana cemetery and

generally others in the Island. Monuments, marble figures, carved gravestones,

tombs in shape of domed mosques, stone slabs over graves surrounded by iron

railings, memorial tablets let into the church walls in the cemetery, and other

mementos of the dead, all in good taste; and the melancholy sound of the wind

through the tall pines made a pleasant impression in one who expected to meet

again the formal and stereotypical form of ovens, one above the other, of the

receptacles for the dead prevailing in other Cuban cemeteries. I walked about

and noticed such names as Agramonte, Aguero, Betancourt, Varona, Mola and other

familiar enough in the annals of the Cuban Insurrection.

We next visited the Plaza San Juan de Dios, where is

situated the Church and Hospital of the same name, built in 1728. Here, in May

1873, at the door of the Hospital as shown in the sketch, the body of the Cuban

hero, Ignacio Agramonte—slain in battle—was deposited as a trophy of war and

exposed to the gaze of the populace for two days. A rumor was current at the

time that the body was not interred, but burned in the cemetery on the night of

the 15th of

We next visited the Plaza San Juan de Dios, where is

situated the Church and Hospital of the same name, built in 1728. Here, in May

1873, at the door of the Hospital as shown in the sketch, the body of the Cuban

hero, Ignacio Agramonte—slain in battle—was deposited as a trophy of war and

exposed to the gaze of the populace for two days. A rumor was current at the

time that the body was not interred, but burned in the cemetery on the night of

the 15th of  May, being first saturated

with petroleum and placed on a funeral pyre of wood. But I could not and dared

not ascertain if the story was true.

The Colonel , however, admitted that the Spanish soldiers are practical

cremationists and had on various occasions burnt the bodies of the dead, but

added that it had always been done for sanitary reasons.

May, being first saturated

with petroleum and placed on a funeral pyre of wood. But I could not and dared

not ascertain if the story was true.

The Colonel , however, admitted that the Spanish soldiers are practical

cremationists and had on various occasions burnt the bodies of the dead, but

added that it had always been done for sanitary reasons.

Continuing our drive the

Colonel pointed out the Governor’s residence, Comandancy General, etc., and we

shortly arrived to the Plaza and Church of San

Fran cisco,

founded in 1599 by Franciscans. All the convents and religious orders were suppressed

in 1842 and this one was used for a while as infantry barracks. It is now devoted to educational purposes

and maintains a college conducted by the Escolapian Fathers. Flags and streamers

were flying from its belfry and windows in anticipation of a coming religious

festival.

cisco,

founded in 1599 by Franciscans. All the convents and religious orders were suppressed

in 1842 and this one was used for a while as infantry barracks. It is now devoted to educational purposes

and maintains a college conducted by the Escolapian Fathers. Flags and streamers

were flying from its belfry and windows in anticipation of a coming religious

festival.

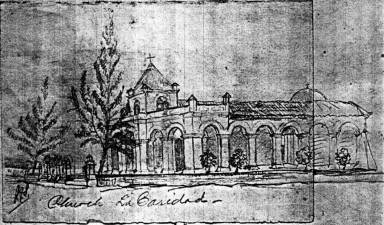

Leaving the square and

winding through a  number of narrow streets we

crossed over the Hatibonico to drive along the wide avenue of La Caridad. Directly on our right was the small and now

abandoned church of La Calendaria, built

in 1806. The Government has, however,

put it to some use by occupying it as a storehouse. The Caridad, as the street

is known, is a wide one, bordered by mango trees, with a narrow walk and

another row of mango

number of narrow streets we

crossed over the Hatibonico to drive along the wide avenue of La Caridad. Directly on our right was the small and now

abandoned church of La Calendaria, built

in 1806. The Government has, however,

put it to some use by occupying it as a storehouse. The Caridad, as the street

is known, is a wide one, bordered by mango trees, with a narrow walk and

another row of mango  trees and benches running

through the middle. Under the portals of the houses to our right and left, we

noticed the sling hammocks and bivouacs of a column of Spanish soldiers which

had come I during the previous night and had been billeted along the road. At

the end of the avenue is the church Nuestra

Señora de la Caridad,[17]

erected in 1809. The church is well built and has a large and well-paved square

and is situated in the middle of a large open space lined with mango trees.

Here it is considered the correct thing to attend mass Saturday morning and

crowds of ladies and their admirers religiously keep up the practice.

trees and benches running

through the middle. Under the portals of the houses to our right and left, we

noticed the sling hammocks and bivouacs of a column of Spanish soldiers which

had come I during the previous night and had been billeted along the road. At

the end of the avenue is the church Nuestra

Señora de la Caridad,[17]

erected in 1809. The church is well built and has a large and well-paved square

and is situated in the middle of a large open space lined with mango trees.

Here it is considered the correct thing to attend mass Saturday morning and

crowds of ladies and their admirers religiously keep up the practice.

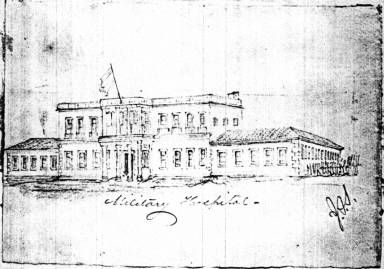

Returning on our track, we

visited the church of San José, built

in 1805, situated near the Plaza de Vapor

and the Military Hospital. This latter building, on account of its size and

purpose, attracted my attention and on a later occasion I visited and walked

through. It had at the time some 1,500 sick, mostly febrile diseases and diseases

of the intestinal functions. Comparatively few wounded, but many soldiers

suffering from ulcer on feet and legs produced by exposure and the hardships of

the march. Large as the building seems

to be, it was inadequate for the number of sick and the Government had been

obliged to convert some storehouses nearby into auxiliary hospitals. As the

close of June there were over 1,700 sick and wounded in the hospitals.

Returning on our track, we

visited the church of San José, built

in 1805, situated near the Plaza de Vapor

and the Military Hospital. This latter building, on account of its size and

purpose, attracted my attention and on a later occasion I visited and walked

through. It had at the time some 1,500 sick, mostly febrile diseases and diseases

of the intestinal functions. Comparatively few wounded, but many soldiers

suffering from ulcer on feet and legs produced by exposure and the hardships of

the march. Large as the building seems

to be, it was inadequate for the number of sick and the Government had been

obliged to convert some storehouses nearby into auxiliary hospitals. As the

close of June there were over 1,700 sick and wounded in the hospitals.

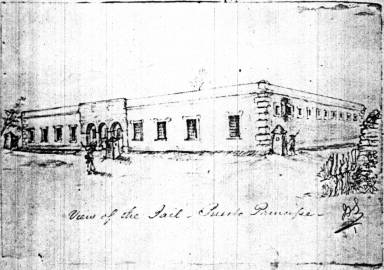

One one side of the Plaza

del Vapor is the railroad station—a veritable large wooden shanty and a

collection of them—and on the other the Public Jail. Here the American Dockray

was confined and on trial for his life on a charge of insidencia[18]. I took considerable interest in the

gentleman’s case and ascertained the following facts. Mr. F. A. Dockray, a gentleman

who had held several government offices in the United States and especially in

Florida, came to Cuba January 1st on a business trip. About the latter part of that month, in a

spirit of adventure and recklessness of consequence, he left Manzanillo

covertly and entered

large wooden shanty and a

collection of them—and on the other the Public Jail. Here the American Dockray

was confined and on trial for his life on a charge of insidencia[18]. I took considerable interest in the

gentleman’s case and ascertained the following facts. Mr. F. A. Dockray, a gentleman

who had held several government offices in the United States and especially in

Florida, came to Cuba January 1st on a business trip. About the latter part of that month, in a

spirit of adventure and recklessness of consequence, he left Manzanillo

covertly and entered  insurgent lines. After

remaining with the insurgents some three months, being constantly with the

chiefs of the Cuban Republic and present at the battled of Naranjo and Guásimas

where it is alleged he took an active part, he succeeded in leaving them and

presented himself on April 3rd at Nuevitas to the U.S. Consular

Agent, who accompanied him to the Governor for the purpose of obtaining a

passport to Havana. Dockray was arrested

and a number of suspicious papers found on him along with several letters addresses

to prominent insurgents in the United States, facts which highly compromised

him. Court martial was ordered in his case and he was condemned to death. I

afterwards learned that the Spanish government has commuted his sentence to the

next lower penalty, and he was sent to Spain to undergo a sentence of ten years

in the galleys at Ceuta, unless fortunate enough to get pardoned out before.

insurgent lines. After

remaining with the insurgents some three months, being constantly with the

chiefs of the Cuban Republic and present at the battled of Naranjo and Guásimas

where it is alleged he took an active part, he succeeded in leaving them and

presented himself on April 3rd at Nuevitas to the U.S. Consular

Agent, who accompanied him to the Governor for the purpose of obtaining a

passport to Havana. Dockray was arrested

and a number of suspicious papers found on him along with several letters addresses

to prominent insurgents in the United States, facts which highly compromised

him. Court martial was ordered in his case and he was condemned to death. I

afterwards learned that the Spanish government has commuted his sentence to the

next lower penalty, and he was sent to Spain to undergo a sentence of ten years

in the galleys at Ceuta, unless fortunate enough to get pardoned out before.

I had got tired of seeing

churches—which all seemed to present much of the same appearance, although the

Colonel said there were two or three more to see—so with a glance at the

Calvary barracks with its fine row of Indian laurel trees in front, and the Beneficiencia—or Foundling Asylum—founded

by a lady—Catalina Betancourt in 1791—we drove to the Casino to obtain the

luxury of an iced drink. Afterwards we walked in the square and listened to the

playing of the band. On such evenings this spot is much frequented by the

ladies and by Spanish Officers—civilians are rare.

A few days later I accepted

the Colonel’s offer of a horse and in the company of several other officers we

rode out early one morning and visited a number of the forts which surround

Puerto Príncipe and are intended to guard it from encroachments of the

insurgents, and protect the zone of cultivation. Riding over the Caridad Bridge

and along the avenue we soon reached

Fuerte Punta Diamante,[19]

about half a mile beyond the Caridad Church on the Santiago de Cuba road. This

is quite a large earthwork of some pretension, surrounded by a palisade and ditch.

It is garrisoned by between 200 and 300 men and armed with a brass sixteen

pounder and a twelve pounder Krupp. I was told that the insurgents were so

daring and came so near on one occasion that a party of them fell upon a

soldier who had gone out from the Fort to forage. In full sight of his

comrades, they cut him to pieces with their

machetes and then galloped off.

A few days later I accepted

the Colonel’s offer of a horse and in the company of several other officers we

rode out early one morning and visited a number of the forts which surround

Puerto Príncipe and are intended to guard it from encroachments of the

insurgents, and protect the zone of cultivation. Riding over the Caridad Bridge

and along the avenue we soon reached

Fuerte Punta Diamante,[19]

about half a mile beyond the Caridad Church on the Santiago de Cuba road. This

is quite a large earthwork of some pretension, surrounded by a palisade and ditch.

It is garrisoned by between 200 and 300 men and armed with a brass sixteen

pounder and a twelve pounder Krupp. I was told that the insurgents were so

daring and came so near on one occasion that a party of them fell upon a

soldier who had gone out from the Fort to forage. In full sight of his

comrades, they cut him to pieces with their

machetes and then galloped off.

Taking bridle paths, we

passed Forts Garrido and Respiro de Agramonte near the road.

Although called forts, these fortifications are properly small block houses and

will hold some twenty to fifty men. Fort Puello

came next, but I did not care to explain that I had already seen this fort,

and came to near being shut up in it.

To the north of the city are

Forts Guayabo, mounting a twelve pounder

Krupp and Rodas, both earthworks surrounded

by ditches and garrisoned by some fifty men. Following an intricate velada, or bridle path for two miles or

more we came upon Fort Polvorin to

the west of the city, near the highway to Havana. Before crossing the Tínima

Bridge, having made nearly the circuit of the city, we passed a second Fort Punta de Diamante and crossing the

bridge the Quinta Simoni where a

detachment of Volunteers were stationed.

Towards the south side of

the city there are forts Serrano, de los

Voluntarios, and a third Punta

Diamante besides a number of fortines,

or small fortified posts. But as the sun was high and hot and ourselves heated

and hungry, we left those to visit on some other occasion and clabbered back to

the Hotel Español for breakfast.

Several days more passed, and having

concluded business which brought me to this part of the Island, I made

preparations to return to Havana. It

was necessary to call at the office of the Comandancia

Mayor to have my passport endorsed.

Here I was fortunate to meet my friend the Colonel, who introduced me to

Lt. Col. Galbis—Chief of Staff commanding General Figueroa and his right hand

man—a talented, energetic and very pleasant officer and gentleman. Several other officers were present and

smoking cigars and lolling in rocking chairs, and it seems that I happened upon

a regular tertulia[20],

for an animated discussion—which my entrance but momentarily interrupted—was

going on among them. The subject was the reports then current concerning

disaffection among the insurgents; the deposition of Salvador Cisneros and assumption

by Máximo Gómez of the Presidency of the Cuban Republic; and the bloody

encounters reported to have occurred, in consequence thereof, between the two

factions of Gómez and Sanguili. As I

had hitherto purposely and carefully refrained from the discussion of any

political or military affairs—as I had found some difficulty in obtaining

information on such, for foreigners seemed to be looked upon with suspicion—I

considered myself fortunate at the opportunity to listen to the unrestrained

utterance of the opinions of those who it would seem ought to be considered

authorities on the question.

It is impossible for Gómez

to “aspire to that position,” said the Colonel, “he is not a Cuban and the

Constitution of the insurgents forbids other than native-born to be elected

President of the so-called Republic.

Besides, Salvador Cisneros, the fab and foolish Marquis de Santa Lucía,

only styles himself ad interim” or

Acting President, “in place of Aguilera. Máximo Gómez is a Dominican, and a

double-dyed traitor. When Spain had the war with Santo Domingo in 1864, Gómez

betrayed his native country and accepted service with us with the rank of

Lieutenant Colonel. He was in Cuba for a while, but when the insurrection broke

out, thinking it offered a wider field for his ambition, he hastened to join

it. His idea is military glory and the

advancement of the African race—he is half Negro anyway—and should it be

possible for him to succeed in his nefarious attempts, Cuba could become a

second Santo Domingo or Haiti, become africanized in fact. And General Lesundis’ saying will prove

true: ‘Cuba will become wholly African when she ceases to be wholly Spanish.’

“If by any fortuitous

circumstance—let us suppose it for the sake or argument, for as a fact no good

Spaniard will admit its possibility—the enemies of Spanish national integrity

should succeed in their designs and Spain— wrecked with internal strife and

struggling fortunes—is forced to give up the Island of Cuba.” Here a general

murmur of dissent ran around the circle.

“We will suppose it for sake

of argument,” continued the Colonel, “the Cubans are utterly incapable of

self-government and anarchy would eventually arise among them. As the only

remedy for salvation and the continuance of their independence, annexation to

the United States would be resorted to. In either case slavery is doomed, and

what would be the result? Haiti and Santo Domingo. With perhaps the repetition

of the barbarous atrocities committed there by the negroes upon the whites. Of

Jamaica with its commerce, energy and agriculture run to seed. The blacks already outnumber the whites in

Cuba and would become the master race once liberty is granted them. The Cuban Republic already has guaranteed

the abolition of slavery, and if Cuba should belong to the United States,

slavery could not of course exist. Free

labor will never flourish.

“Does Spain really want to

finish the insurrection, then let her abolish

slavery in Cuba. Yes, but that would be the immediate ruin and loss of Cuba to

Spain. Very true, and what then? Slavery is doomed anyway, but not so long as

the present situation exists.

I see but one possible

remedy, and that is Cuba freed by the Spaniards themselves.”

Here the Colonel broached a

tender point: The possibility of the Spaniards in Cuba seizing Cuba for their

own, and seceding from the mother country. It is a notorious fact that Prim,

Topete and the leaders of the Revolution of September 1868, if they had failed

in their attempts to overthrow the Government, had the intention of making an

effort to establish themselves in Cuba as an independent government. And the Revolution of September in Spain,

and the Insurrection of October in Yara, have been supposed synonymous events.

When the Colonel got to this

point of his harangue a dozen eager voices interrupted him. I could distinguish

nothing in the babel of sounds which arose. The Chief took the opportunity to

beckon me into an inner office to receive my pass. I thus lost the continuation

of the Colonel’s remarks, but I thought the doctrine of secession a “happy

thought” for Cuba.

While the Chief was occupied

in signing my pass I noticed on a sofa in the corner of  the room a number of leather

pouches, or mail bags, which he informed me had been captured from insurgent

couriers. I did not think it discreet of me to ask him the fate of their

bearers, but could easily guess at it. He laughlighly told me that he called

the contents of the bags—opening and exhibiting several of the papers, letters,

military reports—his novels , for previous to retiring for the night he generally

read a quantity of them, and thus acquired sometimes very useful information; a

few grains of wheat from a bushel of chaff.

the room a number of leather

pouches, or mail bags, which he informed me had been captured from insurgent

couriers. I did not think it discreet of me to ask him the fate of their

bearers, but could easily guess at it. He laughlighly told me that he called

the contents of the bags—opening and exhibiting several of the papers, letters,

military reports—his novels , for previous to retiring for the night he generally

read a quantity of them, and thus acquired sometimes very useful information; a

few grains of wheat from a bushel of chaff.

Seeing that my attention was

drawn to a map of the District lying up on a table with a number of others, he

politely showed them all to me. Every foot of land in the entire district

seemed to have been mapped out, and himself perfectly familiar with it all. He

pointed out the position of the Spanish forces, the strongholds of the Cubans

in the Cubitas and Najasa ranges, and at the Chorrillo where, he said, was to

be found what there was of the Cuban Government. Although the Spanish columns

had for some time been actively employed and almost daily made reconnaissance

in the District, he declared that they never could find but a few struggling

insurgents. The bulk of the Cubans—and

he asserted that altogether there were but three thousand in arms—kept out of

sight. From their elevated points of

their encampments they could always distinguish the march of the Spanish troops

and take pains to keep out of their reach, unless a favorable opportunity would

occur for them to take a swoop in force upon some almost defenseless convoy and

in the surprise of the attack do whatever damage they could. Máximo Gómez with